Jewish Cantors and the Music of the Synagogue

Jascha Nemtsov has been involved in the training of Jewish cantors for many years. In 2008, a cantorial department was opened at the Abraham Geiger College in Potsdam, of which Nemtsov became academic director. In the meantime, cantorial education has been established as a separate course of study at the University of Potsdam, where professionally-oriented lessons in liturgical singing are combined with academic training in Jewish studies, religious pedagogy and the history of Jewish music. Graduates are now working in various Jewish communities in Germany and other European countries.

Many of Nemtsov’s academic publications are dedicated to the music of the synagogue and the work of outstanding Jewish cantors.

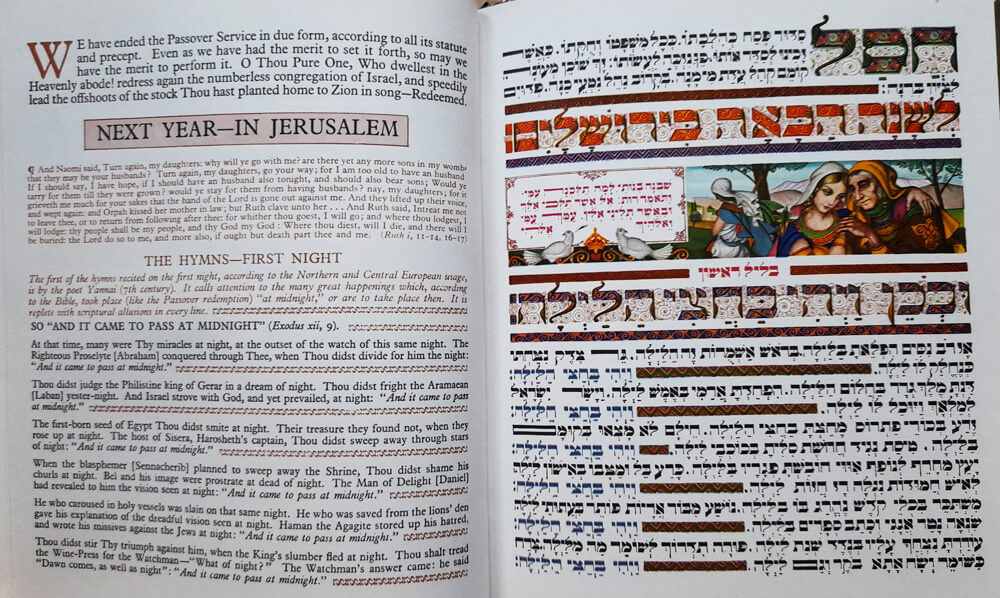

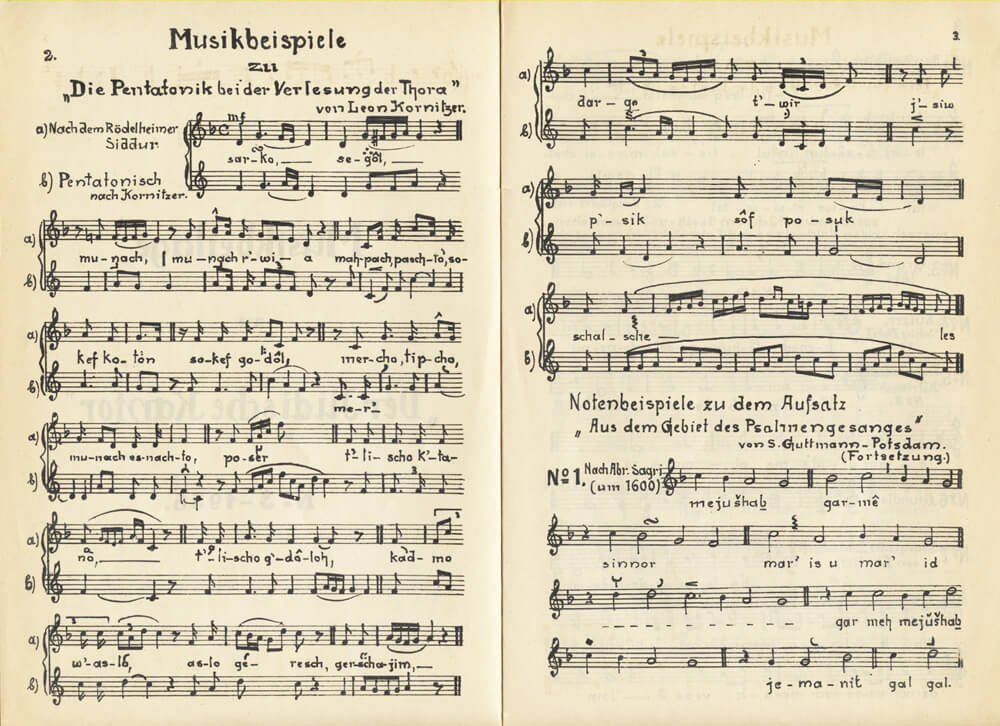

Until the modern era, Jewish religious music was an exclusively oral tradition. While Christian music has been notated since the Middle Ages, the earliest manuscripts of Jewish music date from the 18th century, and the first printed music only from the 19th century. This has mainly to do with different conceptions of music.

In contrast to church music, music in Jewish worship is not associated with an ideal, heavenly harmony, but is seen as an expression of personal devotion to God – a state of mind that is fleeting and cannot be captured with notes. Every person enters into a personal dialog with God. The focus is therefore not on the beauty of the musical form, but on the sincerity and emotional intensity of the prayer.

The individual singing voice as an expression of a person’s religious feelings forms the center of traditional synagogue music. The monophonic chants embody the intimacy and confidentiality of the relationship between man and God.

One consequence of this conception of music is, among other things, the consistent ban on instrumental music. Although the ban on musical instruments in the synagogue is often explained as an expression of mourning for the destroyed Jerusalem Temple, it is in fact more related to the character of Jewish worship. The intimacy of prayer would – according to the traditional view – simply be incompatible with the simultaneous use of musical instruments.

The prayer leader, today often called the “cantor” after the Christian model, was also not intended to occupy an exceptional position in the service, but merely to fulfil an ordering and organizing role – a task that in principle could also be performed by any other member of the congregation. Many Orthodox congregations therefore do without specially-trained prayer leaders. The beauty of the chants is welcomed as long as it is not an end in itself, but is perceived as an expression of devotion (kavanah).

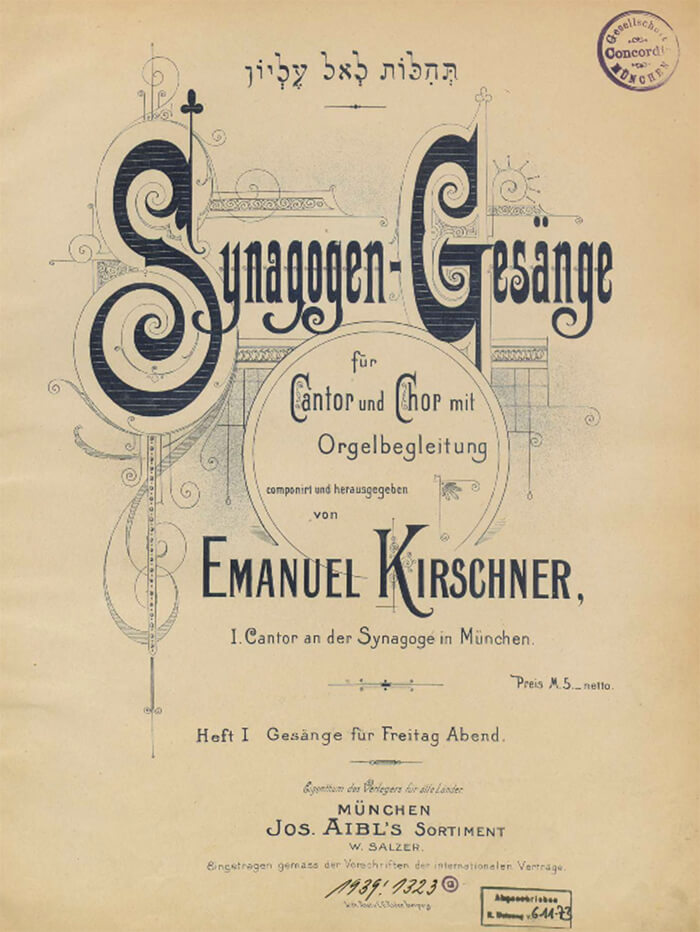

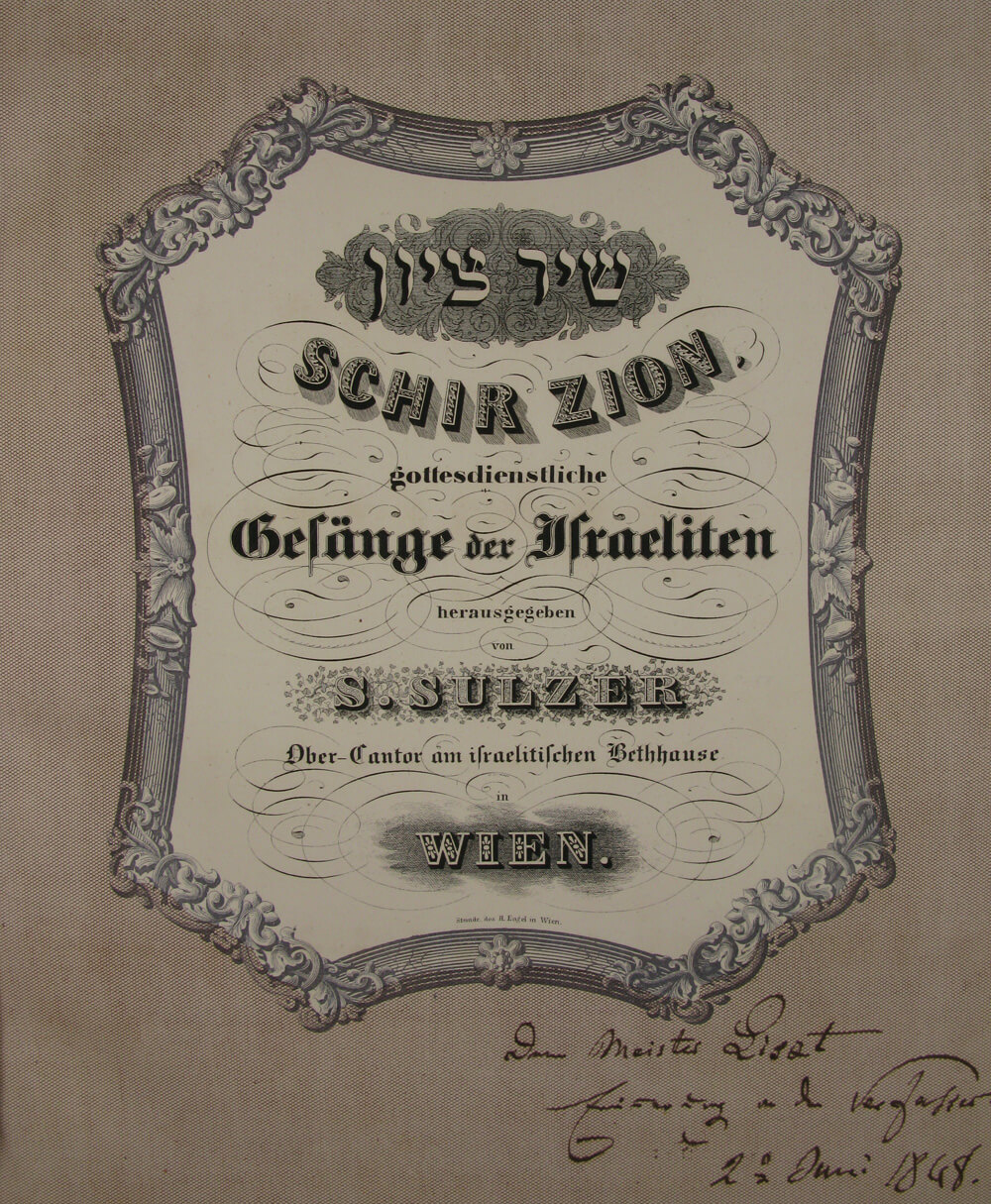

However, the Jewish reform movement founded in Germany in the 19th century contributed to a radical change in synagogue music. The most important composers of the reform movement – Salomon Sulzer in Vienna, Louis Lewandowski in Berlin, Samuel Naumbourg in Paris, Moritz Deutsch in Breslau and Emanuel Kirschner in Munich – were inspired by contemporary Protestant and Catholic church music and developed a style based on the Romantic music of the time. A number of renowned Christian composers were also involved, including Franz Schubert, Ignaz von Seyfried, Joseph Drechsler and Wenzel Wilhelm Würfel.

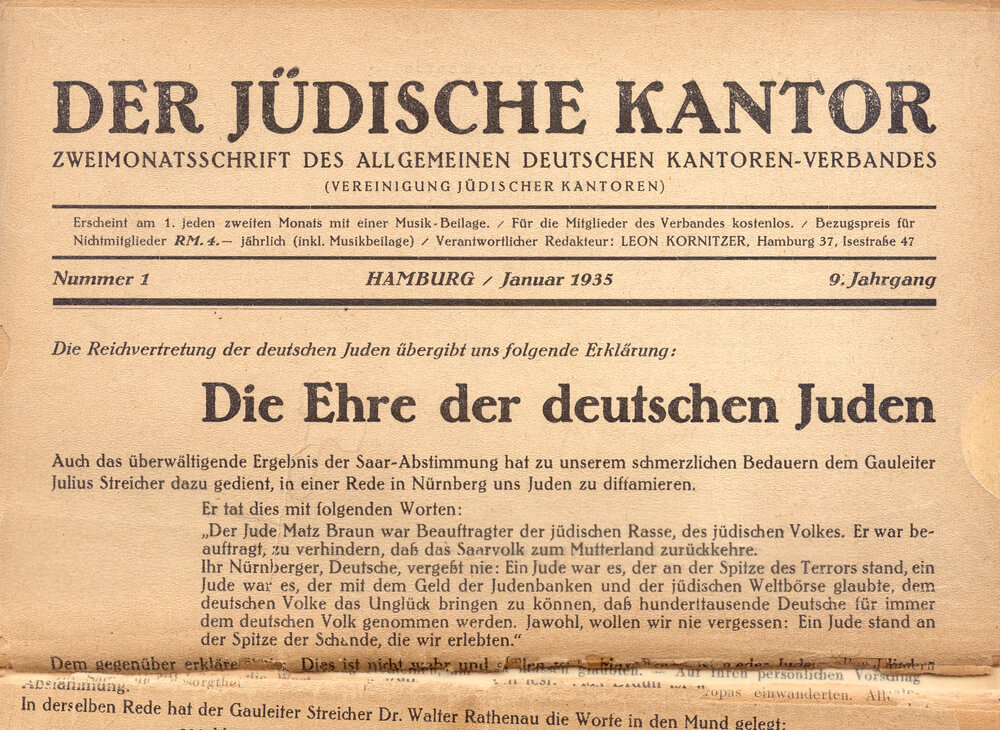

In the words of the Thuringian cantor Hermann Ehrlich (1815–1879), the aim was “uniformity and unity through prayer and song in all synagogues in Germany”. This aesthetic ideal motivated all reformers at the time, as the orally transmitted Jewish liturgical music defied any form of standardization. The transition from the oral tradition to printed editions with collections of synagogue chants was a significant turning point in the history of Jewish music.

One particularly controversial innovation was the introduction of the organ, which was expected to have a “disciplinary” effect. Louis Lewandowski wrote at the time: “The organ, the instrument of instruments, is alone capable of controlling and directing large masses in large spaces thanks to its wide-ranging sonority.” The reform composers, who were trained in European music, now heard the sound of traditional Jewish prayer with the ears of their Christian contemporaries – they perceived it as a disturbance of beauty.

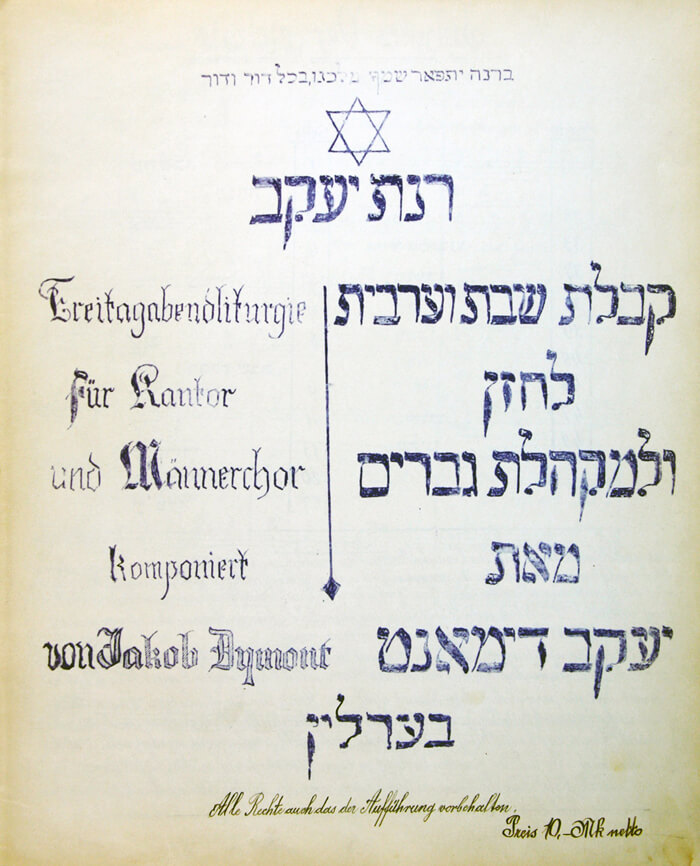

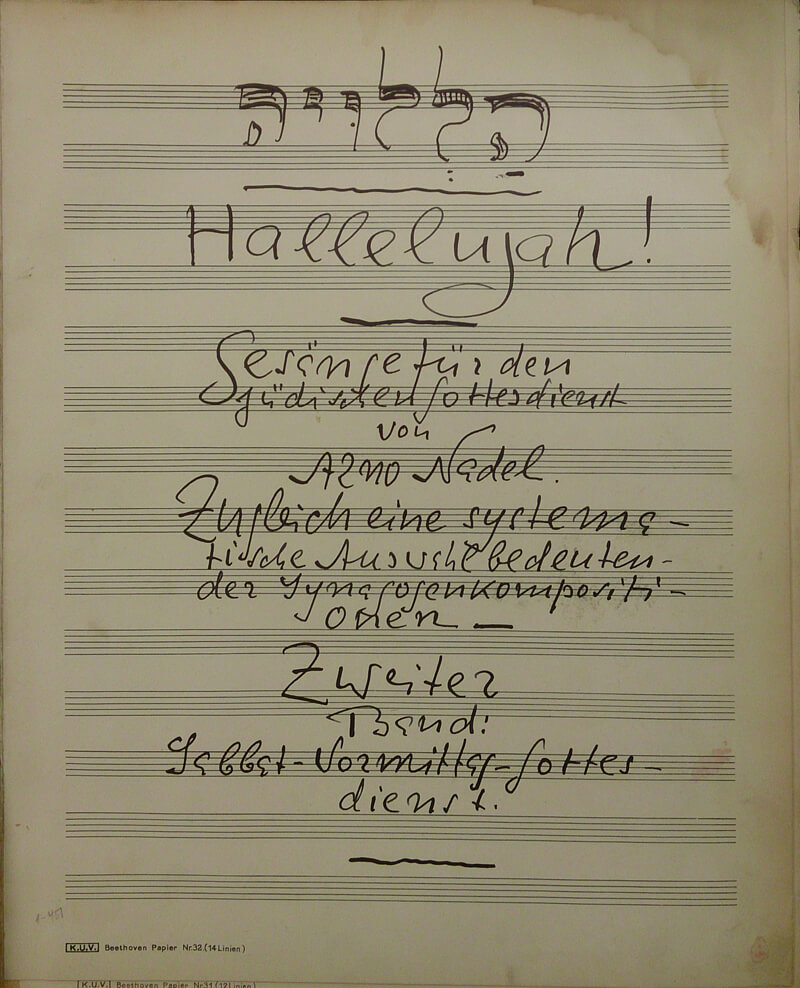

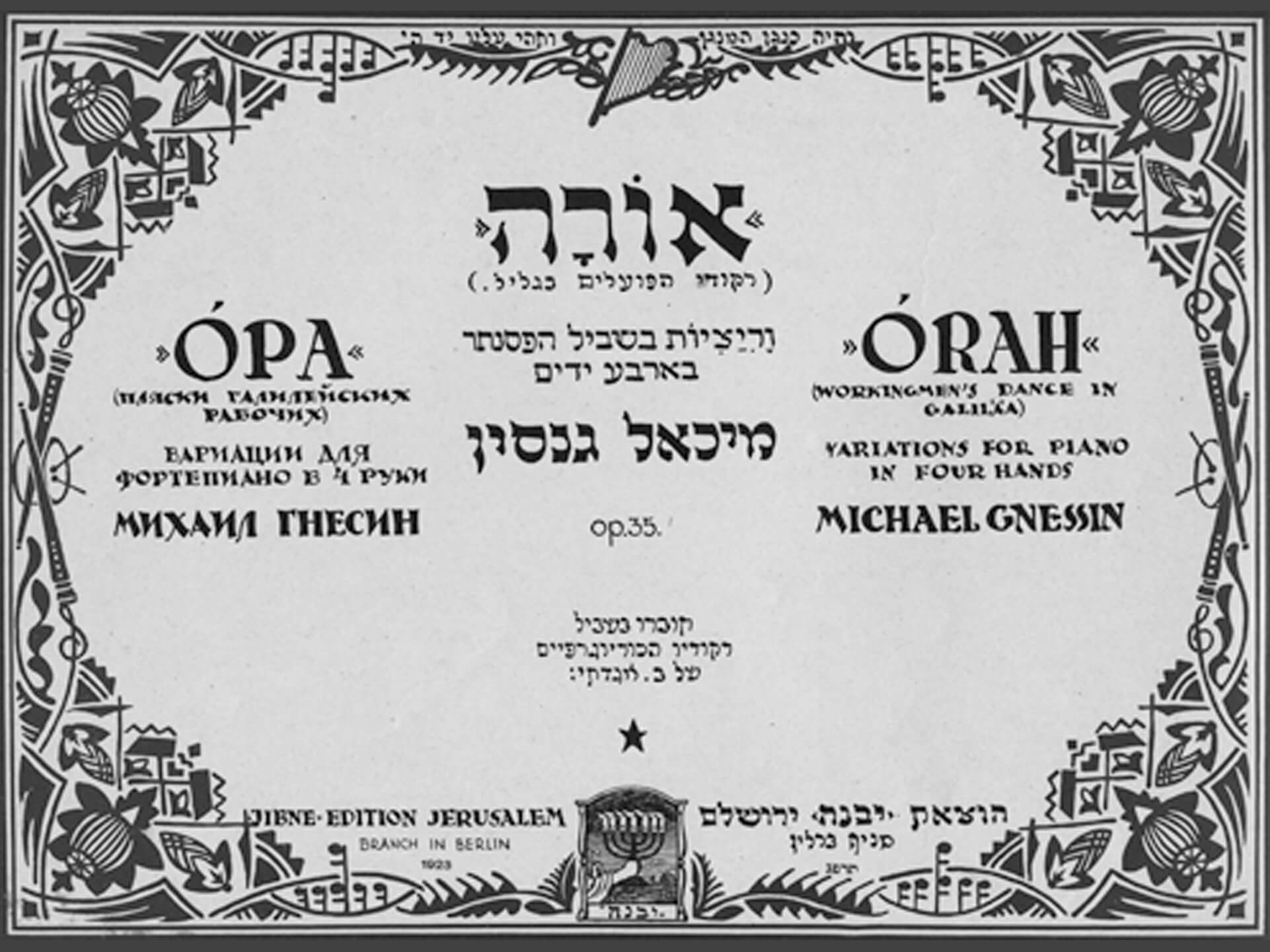

From the early 20th century, under the influence of cultural Zionist ideas, some Jewish musicians began to return to their own musical roots. Such endeavors also became noticeable in the field of synagogue music. The traditional elements that had been neglected in previous decades were now revived and integrated into a contemporary style. In the 1930s, for example, the Jewish Community of Berlin promoted the creation and performance of large-scale liturgical works of this kind, including compositions by Leo Kopf, Jakob Dymont, Heinrich Schalit, Ernest Bloch, Hugo Adler, Jacob Weinberg, Max Ettinger and Oskar Guttmann. A newly-created Friday evening liturgy by Leo Ahlbeck was even performed as late as 1939. However, this promising development was very soon interrupted by the Shoah. The new repertoire, which was largely created under the conditions of Nazi rule, is still waiting to be rediscovered today.